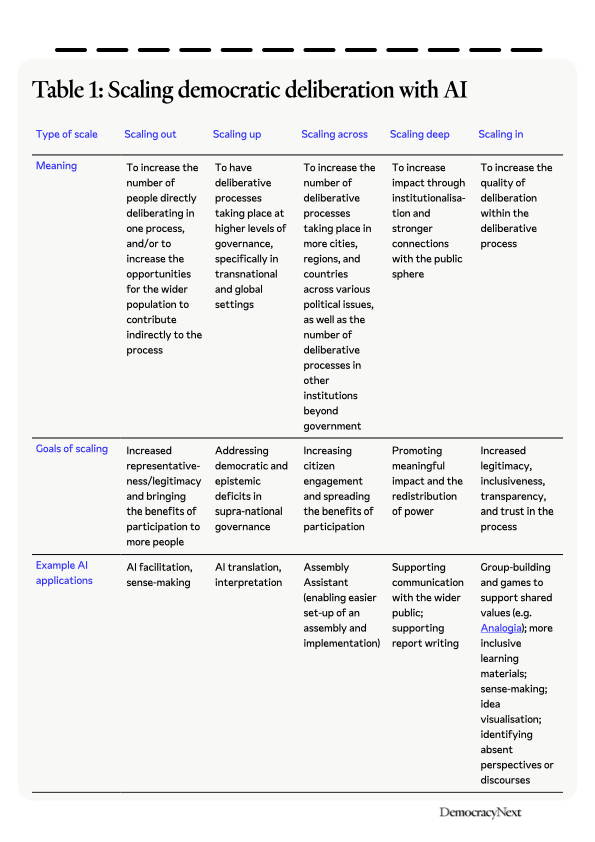

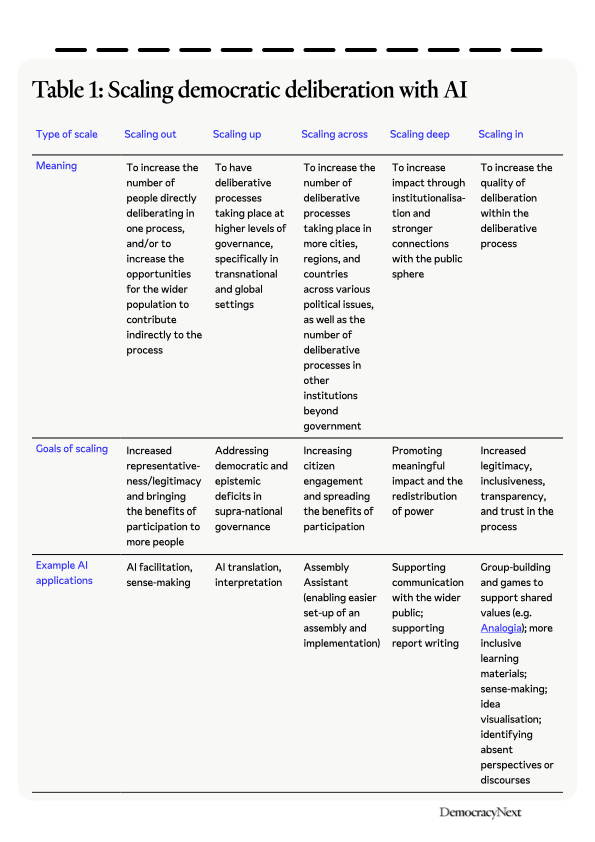

These five dimensions of scale are summarised in the table below:

In the study and practice of deliberative democracy, academics and practitioners are increasingly exploring the role that Artificial Intelligence (AI) can play in scaling democratic deliberation. From claims by leading deliberative democracy scholars that AI can bring deliberation to the ‘mass’, or ‘global’, scale, to cutting-edge innovations from technologists aiming to support scalability in practice, AI’s role in scaling deliberation is capturing the energy and imagination of many leading thinkers and practitioners.

There are many reasons why people may be interested in ‘scaling deliberation’. One is that there is evidence that deliberation has numerous benefits for the people involved in deliberations – strengthening their individual and collective agency, political efficacy, and trust in one another and in institutions. Another is that the decisions and actions that result are arguably higher-quality and more legitimate. Because the benefits of deliberation are so great, there is significant interest around how we could scale these benefits to as many people and decisions as possible.

Another motivation stems from the view that one weakness of small-scale deliberative processes results from their size. Increasing the sheer numbers involved is perceived as a source of legitimacy for some. Others argue that increasing the numbers will also increase the quality of the outputs and outcome.

Finally, deliberative processes that are empowered and/or institutionalised are able to shift political power. Many therefore want to replicate the small-scale model of deliberation in more places, with an emphasis on redistributing power and influencing decision-making.

When we consider how to leverage technology for deliberation, we emphasise that we should not lose sight of the first-order goals of strengthening collective agency. Today there are deep geo-political shifts; in many places, there is a movement towards authoritarian measures, a weakening of civil society, and attacks on basic rights and freedoms. We see the debate about how to scale deliberation through this political lens, where our goals are focused on how we can enable a citizenry that is resilient to the forces of autocracy – one that feels and is more powerful and connected, where people feel heard and empathise with others, where citizens have stronger interpersonal and societal trust, and where public decisions have greater legitimacy and better alignment with collective values.

Against this backdrop, in this paper, we ask: what does scaling democratic deliberation mean, why is it valuable, and what is the role of AI in enabling it?

In answering these questions, we aim to make two core contributions to the field. First, we offer an expanded definition of scale by breaking down the concept across five dimensions: scaling out (increasing deliberator numbers), scaling up (higher governance levels), scaling across (increasing number of processes), scaling deep (increasing impact), and scaling in (improving deliberative quality). The concept of scale is used in various ways across deliberative practice, and we introduce this new typology to overcome this fragmented usage, guide critical discussion, and expand our collective understanding.

Second, we propose that scaling democratic deliberation is not a technological challenge alone, but one that requires a diverse repertoire of technological applications to be developed and fruitfully combined with strengthened civic infrastructure. This provocation aims to guide and stimulate action across the field, emphasising that whilst AI can play a crucial role in scaling deliberation, we must also keep a critical eye on its limitations and risks, and combine it with the civic infrastructure that is necessary for scaling.

We realise that the debate around scaling deliberation, and AI’s role within this, cannot be fully unpacked within one paper. This is a vast topic, requiring significant nuance and ongoing learning across the field, and we aim to encourage and support this collective dialogue. In this vein, this paper is a starting point – one that clarifies what scale means and introduces our stance on AI’s role in enabling it – for a series of papers and reflections exploring different aspects of scale, AI, and democratic deliberation.

Before we dive into our arguments, we want to be clear about the scope of our analysis and how we understand some core concepts. Deliberation means collectively weighing evidence with a goal of reaching a shared decision. Deliberation entails more than just reviewing facts; it requires understanding individual and collective values. That understanding in turn requires feeling the emotions that shape our understanding of the facts, and articulating those values and emotions in relation to our understanding of what is going on in the world. Deliberation is not a mere aggregation of people’s views. Rather, deliberation has two main requirements: it requires citizens to provide reasons and justifications, broadly speaking, for their claims regarding collective action, and it requires citizens to listen attentively and respectfully to others.

The importance of deliberation for legitimate decision-making is grounded in the theory of deliberative democracy, a normative ideal according to which ‘people come together, on the basis of equal status and mutual respect, to discuss the political issues they face, and, on the basis of those discussions, decide on policies that will then affect their lives’ (Bächtiger et al., 2018: 2). Deliberative democrats have long noted that deliberation can occur in various sites across the public sphere – in social movements, schools, and workplaces, to name a few. Deliberation can therefore be understood as a society-wide practice and is not necessarily confined to specific institutional forums.

In this paper, however, we narrow our scope to focus specifically on deliberation taking place amongst diverse groups of citizens in the context of democratic decision-making, especially in the form of deliberative mini-publics. There are many different forms of deliberative mini-publics, including citizens’ assemblies, deliberative polls, and consensus conferences, to name a few (see OECD 2020 for a typology of twelve different forms these processes can take). These processes of democratic deliberation provide spaces for broadly representative groups to influence the policies, regulations, laws, constitutional amendments, or other decisions that affect their lives.

Deliberative mini-publics are defined by two core features: they are composed of an inclusive sub-group of an affected population, and they provide space for structured deliberation enabled by independent facilitation (Ryan and Smith, 2014). In practice, deliberative mini-publics tend to be underpinned by sortition, referring to the use of random selection with stratification across demographic and discursive criteria, as a democratic mechanism to bring a diverse group of citizens together. Deliberative mini-publics provide citizens with the opportunity to learn about the topic at hand through engagement with diverse forms of knowledge, including technical expertise, stakeholder perspectives, and witness testimony. As citizens deliberate on the topic, trained facilitators support citizens in upholding deliberative norms of reason-giving and reciprocity, and help mitigate inequalities between deliberators. Ideally, citizens should have space to influence and shape the process, such as by being involved in agenda-setting, as opposed to processes being engineered from the ‘top-down’.

Given these institutional design features, deliberative mini-publics are often regarded as the leading way to institutionalise deliberative democracy through connecting inclusive and high quality deliberation to sites of power. In this paper, we therefore focus specifically on scaling democratic deliberation through deliberative mini-publics. For clarity, we use the terms deliberative processes and deliberative mini-publics interchangeably.

Deliberative processes can be in-person, virtual, or hybrid. However, we specify that in line with the definition above, we are referring to processes that are largely synchronous – meaning exchanges are happening in real-time – and involve conversation, listening, and reason-giving. While some label purely asynchronous and text-only processes that rely on platforms such as Polis as deliberative processes as well, we do not believe that they meet the definition of deliberation when used on their own. Such platforms constrain participation to voting on and adding statements, which is more akin to opinion-mapping than deliberation in the sense of fostering complex discussion that we have outlined above. This is not to say, however, that these kinds of platforms cannot serve important purposes within democratic governance; they can, including to complement deliberative mini-publics.

The concept of scale can be understood in many ways. Currently, however, we lack a shared vocabulary for engaging with the concept across the field, and that lack of shared vocabulary could undercut critical discussion, informed action, and the co-creation of visions for future practice. For example, within existing scholarship and practice, the concept of scale has, amongst other ways, been understood as referring to the number of people engaged in a deliberative process (Fishkin et al., 2025), the level of governance the process occurs at (Pogrebinschi, 2013) and the effects of the process on the political system (Niemeyer, 2014).

To address this, we introduce five distinct ways that the concept of scale can be understood as it relates to democratic deliberation, especially deliberative mini-publics. This typology draws on the analysis of scale offered in McKinney (2025), as well as recent breakdowns of scale from Arantzazulab (2023) and ScaleDem. These five dimensions of scale are: scaling out, scaling up, scaling across, scaling deep, and scaling in.

These approaches to scaling are not mutually exclusive; a given deliberative process can pursue and instantiate different forms of scale at one time. However, disaggregating the concept of scale allows us to see more clearly its various dimensions, and provides a shared vocabulary for critical engagement.

Furthermore, this typology of scale allows us to see more clearly the kind(s) of scale different AI applications could support, and to move beyond vague claims about AI's ability to scale deliberation. For example, it is common to encounter the claim that AI can enable or support deliberation ‘at scale’. However, what does it even mean to have deliberation ‘at scale’? Does this require a vast majority of a population to participate in the deliberation, or an entire population? Does it require deliberation at a certain level of governance or for the deliberation to have a particular impact? Does it require deliberation of a certain quality? This suggests that what constitutes ‘at scale’ is vague and ill-defined.

We encourage practitioners to be specific about the kind(s) of scale that AI applications are supporting, and the five dimensions of scale introduced below are intended to enable this. For each of the five forms of scale, we also offer some examples of the core AI applications that are relevant to their pursuit.

Scaling out refers to increasing the number of citizens participating in a single deliberative process. Across the field, scale is most commonly spoken about in this way, relating to the ‘headcount’, or the number of people deliberating. Because deliberative processes like citizens’ assemblies typically engage only a small fraction of the population – calling into question their representativeness and legitimacy, and localising their effects to a small group – the goal of scaling out is to broaden participation, bolster legitimacy, extend the benefits of deliberation to far more people, and mobilise wider collective intelligence and capacity for action.

Scaling out can occur in two main ways within deliberative processes. First, it can refer to incorporating many more people directly within the deliberative process. This occurs, for example, in deliberative polls, with recent processes directly incorporating thousands of citizens within deliberations, in contrast to the tens or hundreds of citizens who tend to be directly involved in other forms of deliberative mini-public.

There are many ways that AI can support this form of scaling out, notably through AI facilitation. Despite the many concerns around AI facilitation, some of which we discuss below, in theory it may offer a way to uphold certain deliberative norms across vastly more deliberation groups than human facilitation can, thereby scaling out deliberation to many more people.

Second, scaling out can refer to indirectly incorporating the wider population within the deliberative process through providing opportunities for the public to contribute their stories or perspectives as part of the evidence to be considered by the mini-public. For example, it is possible to use the Cortico methodology and civic technology platform to record many small-group conversations and generate AI-powered sensemaking and highlights that could be shared with both a wider public as well as the assembly. The text-based platform Polis, which uses algorithms to cluster and synthesise inputs, has also been used to bring in contributions from a wider public, either for agenda-setting or gathering perspectives on a deliberation topic (Computational Democracy Project).

Some academics and practitioners have also been focused on using AI for preference aggregation and synthesis across large groups in virtual environments. For instance, the “Habermas Machine” study demonstrates how large language models (LLMs) can be used to create ‘AI mediators’ that help people to find common ground with one another (Tesseler et al., 2024). Generative social choice also leverages LLMs to transform free-form opinion statements into a proportionally representative slate of opinion statements (Fish et al. 2025). These methods arguably stretch the meaning of ‘deliberation’, as, for instance, people are not directly interacting with one another. However, we are interested in exploring how they could be meaningfully combined with (in person) deliberation to enhance decision-making.

Whilst most deliberative processes occur at the local or national level, scaling up refers to applying processes of citizen deliberation to higher levels of governance, specifically the transnational and global levels. Significant democratic and epistemic deficits within transnational and global governance tend to motivate those working on this dimension of scaling, especially as many of the most pressing issues that we face transcend national boundaries.

How deliberative processes can be scaled up to the supra-national level, notably relating to AI and climate governance, has therefore garnered increasing interest. A particularly complex challenge that transnational processes face is effective translation across linguistic divides. AI translation has many shortcomings due to current capabilities, but these are quickly evolving and it will likely be one useful AI innovation amongst others to support deliberative processes to scale up.

Scaling across refers to increasing the number of deliberative processes occurring across democratic systems. Another way of conceptualising scaling across could be as ‘spread’. Scaling across highlights that scale can be a function of the number of deliberative processes that occur across the many decisions that need to be taken by government or other organisations. An important dimension of scaling across is related to how the principles of sortition, deliberation, and rotation can be applied in educational, cultural, economic, and financial institutions.

There is no shortage of important and complex issues that affect citizens’ everyday lives. Deliberative processes, however, are commonly critiqued for being one-off and ad hoc, thereby leaving most of the issues of the day untouched by inclusive citizen deliberation. The importance of scaling across, then, is motivated by the imperative to bring high quality citizen deliberation to the varied issues that affect our lives and to spread the benefits of participation and deliberation more widely across society.

AI could help support scaling across by making it easier for commissioners and facilitators to set up, design, and implement deliberative processes. While AI will never be able to get an assembly set up on its own – it will not remove the necessary relational aspects and the important deliberations needed between key decision makers that are essential for ensuring the process’s impact – there are many repetitive aspects of assembly set-up that could be simplified with AI. For instance, DemocracyNext’s Assembling an Assembly Guide (2023) breaks down the set-up process into three stages and numerous steps with downloadable template documents.

One of DemocracyNext’s next projects is to use AI to transform the guide into an Assembly Assistant that helps an organiser with understanding the various stages and chronology of steps involved, as well as in preparing key documents such as those needed for procurement, invitation letters, establishing governance committees, etc. Such a tool is being developed in the aim of serving the higher order goal of enabling assemblies to scale across more quickly and easily, and would have transferable uses for other contexts beyond government as well.

Scaling deep refers to increasing the impact of deliberative processes on political systems, with stronger connections to decision-making and greater influence on the public sphere. Deliberative processes are sometimes criticised for their limited impact on democratic governance, which can lead to these processes being viewed as ‘tokenistic’ and instances of ‘participation washing’. Scaling deep is essential to ensure meaningful deliberation by actively redistributing political power and connecting to broader public discourse and debate, in the context of government and other institutions.

In the literature as well as in practice, scaling deep is often talked about as institutionalising deliberative processes, where the goal is to anchor/embed/make permanent the deliberative process as a normal way of decision making. Institutionalisation usually entails clarifying and strengthening the relationship of the new deliberative body with other key bodies, such as elected representative institutions and public administrations in the context of government. In other contexts, it may mean strengthening the relationship with the organisation’s board, leadership, membership, or other relevant groups.

The way that AI can support scaling deep is not particularly obvious, and it is even questionable whether that is the right way to be thinking about how to enable institutionalisation. From experience, it is first and foremost a relational and context-dependent task, necessitating many conversations with all relevant stakeholders – typically across partisan lines – and a process ensuring buy-in from across the system. That said, there are a few different ways that AI could be used to support some aspects of scaling deep, such as by enabling better communication with the wider public, or supporting deliberators in formulating more substantive and implementable recommendations. These applications could reduce gaps and frictions between assembly outputs, administrator actions and the wider public sphere, hopefully resulting in better uptake and impact.

Lastly, scaling in refers to increasing the quality of deliberation within the deliberative process. Research and practice has long established how certain design choices within deliberative processes can support higher levels of deliberative quality, including skilled facilitation to navigate inequalities, diverse and accessible learning materials to support informed discussion, and group building activities to strengthen trust and enable people to better grapple with complexity (OECD, 2020; Niemeyer et al., 2023). However, deliberative processes can suffer from a number of procedural shortcomings, such as low facilitation quality, non-inclusive learning materials, or poor information processing, amongst many others.

Scaling in refers to steps being taken to address and overcome these procedural challenges to enable higher quality deliberation within the process. This could include, for example, AI applications that assist humans in facilitating discussions, accurately summarise and synthesise deliberative content, identify absent perspectives/discourses, or promote more interactive and inclusive learning amongst diverse citizens. Whilst this is not a commonly discussed feature of scale in relation to deliberation, we believe that focusing on how to scale the deliberative quality of processes is a crucial dimension for consideration.

As a field, we are still at the very early stages of exploring the role of AI within democratic deliberation, yet the speed of AI development and its potential to transform many aspects of society presents an urgency to our task. As a result, there is so much learning and experimentation that is required to effectively navigate the opportunities and challenges that AI integration brings. We hope that by breaking down these five dimensions of scale, identifying their goals, and outlining some potential AI applications to support them provides a shared vocabulary for the field to more precisely and effectively grapple with AI’s role in scaling democratic deliberation.

Now, we offer some reflections on the role that we see for AI in supporting meaningful future trajectories for scaling democratic deliberation. In particular, we make two points: (a) whilst keeping a critical eye on AI’s limitations and risks, we should develop a broad repertoire of deliberative technologies that can support these dimensions of scaling; and (b) beyond technological innovation, we should develop the civic infrastructure that is necessary to support real-world impact from tech-enhanced deliberative processes. We realise that we cannot unpack these points fully here; each is raised with corresponding areas for future research that we intend to pick up in subsequent publications.

Within the field today, much of the energy is going towards how we can use AI to directly scale out democratic deliberation to many more people. This has been reflected in the academic literature, where scaling is often synonymous with headcount. Scholars and practitioners have also been increasingly interested in mass online deliberation platforms and artificial facilitation.

We are concerned that using AI to scale out deliberation in this way may hollow out the richness of deliberative processes and mean that we lose sight of the first-order goals outlined in the introduction, such as strengthening collective agency for the sake of improving democratic resilience. In particular, building trust, understanding and a sense of togetherness – all core components of quality deliberation – takes space, time, and energy. It requires citizens being able to claim ‘ownership’ over the conditions under which they are deliberating, such as by setting the agenda for the deliberative process and establishing the norms of communication. It also requires citizens being able to bond and learn from one another between formal sessions, such as over coffee or walking between venues. We have seen so many cases in practice where bringing diverse groups of people from all walks of life into a shared space can be a transformative experience for those involved. As group sizes scale out through the deployment of AI, we are concerned that these relational dynamics that are so crucial for promoting quality deliberation, building trust, and mending the fabric of democracy will be far harder to enable.

Although we understand that there are notable critiques of smaller-scale forums, we also believe that there is something necessary and important about them: they provide the unique conditions for high quality deliberation amongst diverse groups that are otherwise rare in democratic systems, and enable transformative kinds of relationships and experiences that are much harder to promote as processes scale out.

That said, we do not oppose explorations of using AI to scale out democratic deliberation; there are significant considerations around how scaling out could help close potential legitimacy deficits in deliberative processes, and technological advancements may alleviate some of the concerns we have raised. Indeed, amongst other things, research suggests that scaled out processes can support more reflective voting at elections (Fishkin et al., 2025), and there are important ways AI could be used to enable indirect input from the wider public into deliberative processes. As such, at this very early stage of exploration, there is plenty of space for more learning and experimentation around using AI to scale out deliberation.

Rather, our core point is that we need to develop a broad and critically-informed repertoire of deliberative technologies that support and complement deliberative processes across the five dimensions of scaling. A holistic view of scale should guide technological innovation, and this should be reflected in broader explorations around the role that AI can play in increasing the quality, impact, and number of deliberative processes, as well as the number of citizens they reach.

Furthermore, just as we presented some concerns around using AI for scaling out, we must also take this critical eye to any other instance of AI integration into the deliberative process. Amongst other things, limited transparency, the excessive influence of technology, problematic biases, and how citizens perceive AI integration are all essential considerations, and the effects of AI integration need to be carefully weighed up with the specific context and goals of a given deliberative process (McKinney, 2024). Therefore, as we expand our repertoire of deliberative technologies across these dimensions of scale, we also need to expand our critical understanding of the new concerns and challenges that AI integration brings, and reflect on the extent to which these can be navigated effectively.

To this end, an important next step for action-orientated research is to rigorously map out and critically analyse AI applications across the full life cycle of deliberative processes whilst keeping this holistic understanding of scale in mind. From process planning and inclusive learning to quality deliberation and meaningful impact, what AI applications could help address existing challenges facing deliberative processes, what kind(s) of scale do they support in doing so, and what critical concerns do they raise?

To answer these questions, we plan to convene technologists and deliberative democracy experts to do a critical analysis of potential AI applications across the full life cycle of deliberative processes and map these onto the five dimensions of scaling identified. Next steps beyond that could be to develop an empirical evaluation framework for assessing AI’s impact across the five dimensions, and to develop guiding principles for navigating the opportunities and risks that AI integration brings to deliberative processes.

Ultimately, our aim is to extend our collective understanding, and guide practitioner innovation, around a broad repertoire of deliberative technologies to support a holistic and critically-informed approach to scaling democratic deliberation with technology.

Expanding the repertoire of deliberative technologies is a necessary step towards meaningfully scaling democratic deliberation, though it is not sufficient in itself. Scaling democratic deliberation is not susceptible to a technological fix alone; it requires careful technological integration alongside broader processes of social and political change. We cannot overlook the contextual, relational, and time-intensive work that is required to advocate for, deliver, and connect high-quality deliberative processes to decision-making for sustained impact across governance issues. Discussions of AI’s role in scaling democratic deliberation should not overlook this, and therefore we need to centre the combination of the technological and ‘non-technological’ in meaningfully scaling democratic deliberation.

Even if we could use AI to scale out democratic deliberation to the ‘masses’, this can only ever form one part of the broader challenge of meaningfully scaling deliberation. Deliberative processes should also be connected to and influence sites of power, encourage participation and engagement from the politically marginalised, and occur across a plurality of political issues that affect our lives. Whilst AI and future AI advances may be able to help address these challenges, they are not simply technological challenges; they require civic infrastructure to support real-world change and impact. For example, amongst many other considerations, we need to deepen and strengthen connections between deliberative bodies and public officials, grow peer-to-peer learning and community networks across and within policy issues, and develop and promote the political and social mechanisms that support and equip individuals from across society to participate in deliberative processes.

There are limits to AI’s potential for scaling deliberation, and therefore exploring the civic infrastructure that is required for catalysing scaling is necessary. To this end, in a forthcoming paper we are planning to do a deep dive into what we consider as a leading example of robust civic infrastructure for scaling deliberative practice: Arantzazulab, a democracy innovation lab in Spain’s Basque Country.

Launched in 2020, they have achieved outsized impact in a short period of time. Arantzazulab plays a key role in institutionalising citizens’ assemblies and other forms of deliberative processes, nurturing cross-regional and cross-sectoral networks, facilitating peer-to-peer learning, conducting research, and storytelling. Their co-governance, operating, and co-funding model is unique, and they have a physical presence, which are both likely contributors to their success.

Five years ago, there were no assemblies in the Basque Country. Today, thanks to Arantzazulab’s efforts, there are examples of one-off and permanent assemblies at local and provincial levels, the Basque autonomous community government is exploring how to incorporate deliberative democracy in their way of engaging citizens and the energy and climate change legislation suggests the creation of a permanent climate assembly. Furthermore, more municipalities have expressed interest in establishing assemblies, the number of people with facilitation and organisation skills has multiplied, and Arantzazulab – in a collaboration with DemocracyNext – is also spreading the ideas of sortition and deliberation to Mondragon Corporation, where there will be experiments in two cooperatives to apply the principles of deliberative democracy to their governance and decision-making in 2025. Such scaling efforts require deep relational and strategic work.

In our next paper, we intend to unpack the mechanisms that are behind the success of this model, distinguishing between what can be replicated elsewhere and what is context-specific to the Basque Country. We may also explore a few additional examples, such as We Do Democracy in Denmark, to further expand our understanding of the crucial role that civic infrastructure plays in catalysing scaling beyond and alongside AI.

The intersection of technology and democracy represents one of the most consequential challenges of the 21st century. As technologies like AI develop rapidly, we face critical choices about how they will shape – or undermine – our democratic futures. In this paper, we have offered a foundational framework for investigating the scaling of deliberative processes across five dimensions, moving beyond simplistic notions that equate scale merely with participant numbers.

Our analysis reveals that meaningful scaling requires a balanced approach. First, we must develop a diverse technological repertoire that addresses all five dimensions of scale – not just increasing headcount, but also enhancing quality, expanding reach, deepening impact, and elevating governance levels. Second, these technologies must be embedded within robust civic infrastructure that can support the relational, contextual work essential to deliberative democracy. Technology alone cannot scale deliberation without the supporting social, cultural, and institutional structures.

This balanced approach carries significant implications for practice. Deliberative practitioners should resist the temptation to pursue any single dimension of scale at the expense of others. Instead, they should identify which dimensions are most relevant to their context and develop complementary strategies across technological innovation and civic infrastructure building. Funders and policymakers, meanwhile, should support this holistic vision by investing in both technological experimentation and the civic infrastructure needed to ensure these innovations translate to real-world impact.

For researchers, our framework offers a structured way to evaluate AI applications in deliberative contexts. Future research should examine not only how technology can support each dimension of scale, but also how these dimensions interact and potentially compete with one another. Other questions to consider are: what are the barriers to realising these different dimensions of scale, and what is gained and lost in the process when scaling? Our next papers will map out different AI applications across the five dimensions of scale, and expand upon the civic infrastructure that successfully contributes to scaling democratic deliberation.

The path toward scaled deliberation will ultimately require bridging technological innovation with democracy's fundamental human elements – trust, connection, understanding, and collective agency. By embracing this hybrid approach, we can work toward a democratic future where technology enhances rather than replaces the rich interpersonal dynamics at the heart of effective deliberation, helping to build democratic resilience in an increasingly complex world.

We received valuable feedback and questions during a virtual roundtable that we convened in collaboration with Andrew Sorota from the Office of Eric Schmidt in April 2025. We want to thank those who participated and provided written comments on our first draft: Ione Ardaiz; Matthew Botvinick; Nicole Curato; Dimitra Dimitrakopoulou; Joseph Elborn; Daniel Fusca; Yasmin Green; Ian Klaus; Hélène Landemore; Jane Mansbridge; Aviv Ovadya; Lex Paulson; Ariel Procaccia; Kyle Redman; Manon Revel; Kris Rose; Hollie Russon-Gilman; Lukas Salecker; Alice Siu; Audrey Tang; Glen Weyl, and Eugene Yi.

We are also grateful to everyone who provided feedback on our second draft: Oliver Escobar; Iñaki Goñi; Jenny Mansbridge; Arantxa Mendiharat; Kyle Redman; Audrey Tang; Glen Weyl; Stefaan Verhulst; and Matthew Victor.

Thank you to DemocracyNext colleagues for their thoughtful feedback as well: Ruba Asfahani; James MacDonald-Nelson; Lucy Reid, and Hannah Terry.

Arantzazulab. 2023. Design for Democracy Innovation. https://ezagutzataria.arantzazulab.eus/wp-content/uploads/Design-for-Democracy-Innovation.pdf.

Bächtiger, A., Dryzek, J.S., Mansbridge, J. and Warren, M., 2018. Deliberative democracy. The Oxford handbook of deliberative democracy, pp.1-32.

Fish, S., P. Gölz, D.C. Parkes, A.D. Procaccia, G. Rusak, I. Shapira, and M. Wüthrich, 2025. Generative Social Choice. arXiv:2309.01291.

Fishkin, J., Bolotnyy, V., Lerner, J., Siu, A. and Bradburn, N., 2025. Scaling Dialogue for Democracy: Can Automated Deliberation Create More Deliberative Voters?. Perspectives on Politics, pp.1-18.

McKinney, S., 2024. Integrating artificial intelligence into citizens’ assemblies: Benefits, concerns and future pathways. Journal of Deliberative Democracy, 20(1).

McKinney, S. 2025. The politics of scaling deliberative mini-publics (with AI): A critical and clarifying typology. Available upon Request.

Niemeyer, S., 2014. Scaling up deliberation to mass publics: Harnessing mini-publics in a deliberative system. Deliberative mini-publics: Involving citizens in the democratic process, pp.177-202.

Niemeyer, S., Veri, F., Dryzek, J.S. and Bächtiger, A., 2023. How deliberation happens: enabling deliberative reason. American Political Science Review, 118(1), pp.345-362.

OECD, 2020. Innovative Citizen Participation and New Democratic Institutions: Catching the Deliberative Wave, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/339306da-en.

Pogrebinschi, T., 2013. The squared circle of participatory democracy: Scaling up deliberation to the national level. Critical Policy Studies, 7(3), pp.219-241.

Ryan, M. and Smith, G., 2014. Defining mini-publics. Deliberative mini-publics: Involving citizens in the democratic process, pp.9-26.

Tesseler, M.H., M.A. Bakker, D. Jarrett, H. Sheahan, M.J. Chadwick, R. Koster, G. Evans. L. Campbell-Gillingham, T. Collins, D.C. Parkes, M. Botvinick, and C. Summerfield, 2024. AI can help humans find common ground in democratic deliberation. Science 386(6719). DOI: 10.1126/science.adq2852.

About the co-authors:

Sammy McKinney is a PhD student in Politics and International Studies at the University of Cambridge and an AI and Deliberation Fellow at DemocracyNext. His PhD research critically explores the integration of artificial intelligence into processes of public deliberation, especially citizens’ assemblies. This research expands on his master's thesis carried out at the University of Edinburgh, which he published in an adapted form in the Journal of Deliberative Democracy. Beyond academia, Sammy has facilitated AI governance courses for BlueDot Impact, co-developed ethical guidelines for AI in public deliberation with deliberAIde, and planned tech-enhanced conservation projects with partners from across the globe through Rainforest Connection.

Claudia Chwalisz is Founder and CEO of DemocracyNext. She has spent over a decade working on democratic innovation, beginning with research on populism and citizens' disillusionment with politics. She co-leads the Pop-Up Lab on Tech-Enhanced Citizens’ Assemblies with the MIT Center for Constructive Communication. Claudia led the OECD’s work on innovative citizen participation from 2018–2022, where she developed the Deliberative Democracy Toolbox and co-authored key reports and standards. Claudia played a central role in designing the world’s first permanent citizens’ assemblies and has advised governments and institutions globally on deliberative processes. She is an Obama Leader, and serves on advisory boards including the UN Democracy Fund, The Data Tank, and MIT’s Center for Constructive Communication. She is also the author of The Populist Signal and The People's Verdict.

How to cite this paper:

McKinney, Sammy and Claudia Chwalisz (2025). “Five dimensions of scaling democratic deliberation: With and beyond AI”, DemocracyNext.